When former Governor of Virginia Terry McAuliffe announced his candidacy for reelection in December 2020, it looked like the race was his to lose. In a country still reeling from the behavior and effects of the Trump administration, the decision made profound sense — Americans had just voted to promote center-left career politician Joe Biden to the White House, additionally handing Democrats control of both the House and Senate to overwhelmingly reject the conservative politics of the last four years. Virginia itself continued to boom under eight years of Democratic state leadership and had voted blue in four consecutive presidential elections. McAuliffe, a longtime friend of Biden’s with a demonstrated track record of progressive success in Virginia, seemed an obvious choice for the Democratic party — and the state.

But it all fell apart. And now Glenn Youngkin, businessman and former co-CEO of private equity company the Carlyle Group, will metaphorically repaint the Virginia Governor’s Mansion red when he takes office next year. Despite launching his campaign without any remarkable name recognition or platform, Youngkin managed to deftly and successfully out-maneuver his competition, gradually closing an initial gap in polls and ultimately freewheeling to victory on election day.

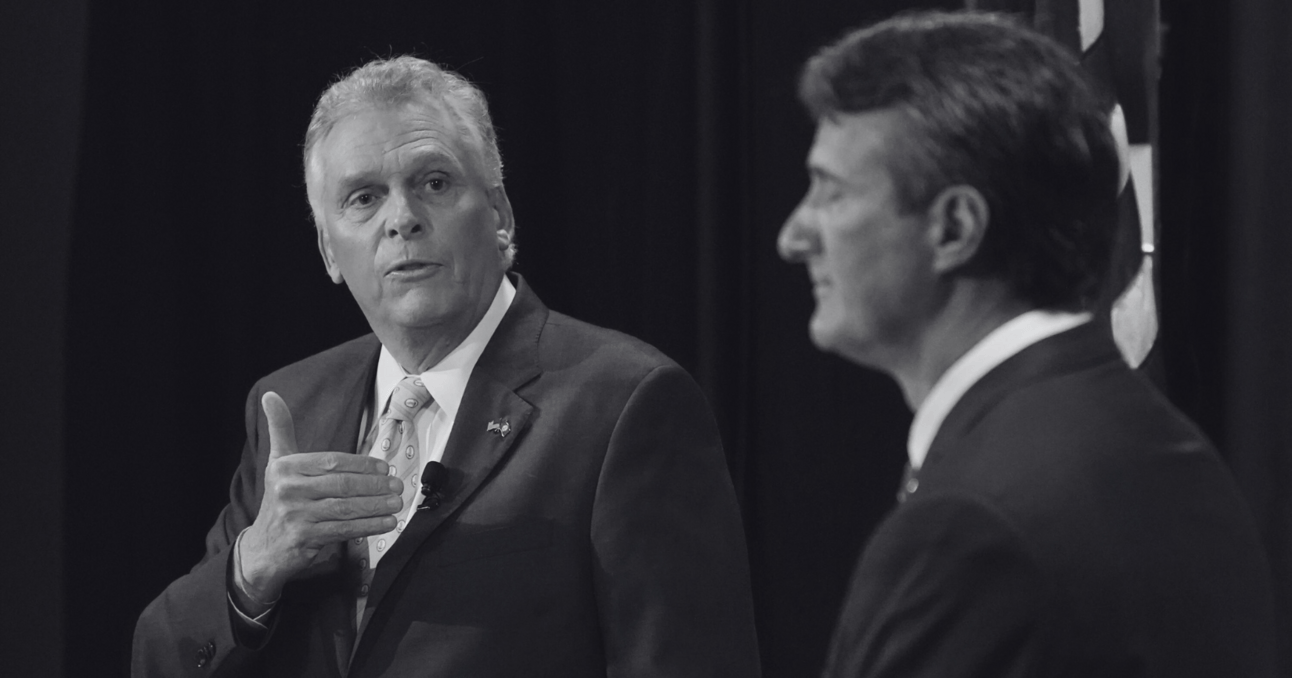

It all begs one basic, unavoidable question: What happened? How did the relatively unknown Glenn Youngkin manage to beat early frontrunner Terry McAuliffe, an established Virginian politician who won every single district in the Democratic primary?

It’s a difficult question to answer. And it’s especially difficult to pinpoint any one thing that Terry McAuliffe, or his campaign, did wrong in their race to reclaim the Virginia governorship. Sure, you could point to a national political landscape that grew increasingly hostile toward Democrats as the race dragged on; Biden’s handling of Afghanistan (among other hot-button issues) undeniably contributed to McAuliffe’s slippage in election polls. Or you could dig into Virginia’s mildly confusing political history as a state that swings, seemingly randomly, from blue to red — and vice versa — in local and regional elections. Or, if you wanted to lay the blame at McAuliffe’s feet personally, you could condemn him for publicly saying that he doesn’t “think parents should be telling schools what they should teach” (which top Youngkin campaign strategists have already highlighted as a key turning point in the race). Or you could give credit to Glenn Youngkin himself, a uniquely ideal gubernatorial candidate produced by an unconventionally egalitarian Republican primary process.

If you wanted to claim that any one of these factors cost McAuliffe the race, you could, and you’d be correct — partially, anyway. As is often the case in electioneering, it’s more likely an unfortunate combination of these events and phenomena (rather than any one thing) that brought McAuliffe’s campaign to its disagreeable end.

A Hostile National Political Landscape

When McAuliffe first began to lose ground in Virginia, pundits immediately tied the slippage to President Biden’s plummeting national approval ratings. It’s an explanation that made a lot of sense at the time — political friendship and similarities with Biden aside, McAuliffe also made a very early, conscious effort to nationalize the gubernatorial race, hoping to connect Youngkin with Trump (a deeply unpopular figure who lost the state by 10 points in the 2020 presidential election). But in doing so, McAuliffe also inadvertently linked himself with his national political counterpart; when President Biden began to lose ground in the summer of 2021, it made a certain amount of sense to expect a parallel slide in the Virginia gubernatorial race.

“Biden’s slippage in the polls is the number one driver of what’s happening right now,” Richmond-based communications consultant Tucker Martin said in a late October interview. “Before Afghanistan, you saw this race was an eight-point race, a nine-point race. Biden’s numbers were very solid. What happened in Afghanistan — as crazy as it is, and McAuliffe had nothing to do with it, and it’s not his fault — has had a huge impact on why the race has tightened.”

And crisis in Afghanistan was far from the only hot-button issue that landed Democrats in the hot seat. Following a summer in which it appeared that we might finally end the Covid-19 pandemic, its resurgence kindled general resentment on a mass scale — and since Democrats were in charge, they were found responsible.

“Covid restrictions and personal liberty are a big issue [for me],” one voter at Richmond City Public School George Carver Elementary School told me on election day, who wished to remain unnamed due to her high-profile profession. “I’ve been a Democrat my whole life, and I’ve always voted Democratic until this election until this election. This is the first time I’ve ever voted for a Republican. I’m wondering if there are more voters like me…I know anecdotally that people are not happy with the way the pandemic has been handled and the way things are going under Democrats.”

And apparent national Democratic dysfunction only exacerbated things. While President Biden has now officially signed the $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill into law, making good on a key part of his economic platform, legislators’ inability to push the policy through the House and Senate before the Virginia gubernatorial election noticeably undermined McAuliffe’s talking points regarding Democratic Party successes. Whether this congressional gridlock impacted the Virginia statesman’s campaign in any way measurably worse than other phenomena is still undetermined, but it does seem profoundly likely that it had some real effect on the race.

A Fickle State Electorate

If a national political atmosphere hostile to establishment Democrats was bad for McAuliffe, it was compounded by the fickle nature of the Virginian electorate. Virginia consistently elects governors of the party opposite to the one in the White House — the only exceptions to that rule being McAuliffe himself in 2014, when he won under the Obama administration, and A. Linwood Holton, Jr., who won the governorship in 1969 while Republican Richard Nixon held the presidency.

“I think this was always…going to happen,” Executive Director of the Democratic Party of Virginia Andrew Whitley said in an interview shortly before election day, discussing the closeness of the race. “I think it was always going to happen. I’m comfortable with saying this is a Democratic state, particularly in presidential elections, but it sort of shifts to purple in state and more local elections.”

And Whitley wasn’t the only one to highlight the fickle nature of the Virginian electorate. Martin went even further, drawing direct parallels to one particular past gubernatorial election to describe patterns and trends he saw repeating themselves (albeit with one crucial difference).

“This feels closer to 2014 than ’09,” Martin said. “I go to ’14 because you see a national environment that’s very favorable for the Republican, but still a very, very close race — the fundamental difference being, Ed Gillespie ran out of money. Glenn Youngkin…he has the funding, which is a huge advantage, because a big part of politics is: If that wave does come along, can you actually catch it?”

Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney made the same comparison, talking to reporters and voters at a McAuliffe get-out-the-vote (GOTV) event in Henrico County. But unlike Whitley or Martin, Stoney shared a strong sense of optimism that McAuliffe would still manage to grind out a victory, even despite the changing winds.

“It doesn’t feel like ’09,” Stoney said. “It just feels more like 2014…There’s gonna be a lot of egg on a lot of people’s faces come Tuesday night — and I’ll be ready to apply the egg.”

It’s also worth noting that this Virginian electoral volatility isn’t an esoteric phenomenon. It’s something that many voters know about — and actively think about — when heading to polls.

“Virginia is weird,” high school history teacher Cluny Brown, 57, said after casting her vote for McAuliffe at the Adult Education Center in Henrico County. “When it comes to polling, quite often, the state does not go the way the polling says. It’s not as close as people think it is.”

Candidate Glenn Youngkin: Not Donald Trump (or Ken Cuccinelli)

When the Republican Party of Virginia set out to define their nomination process for this most recent gubernatorial election, they took pains to prevent a Trump-loyalist from winning — not only deciding to hold a convention rather than a primary, but even implementing a form of ranked choice voting (an increasingly popular balloting system requiring that a winner secure a majority of votes, not just a plurality). And it worked.

“Glenn Youngkin just does not come across like Donald Trump,” Martin said. “I’m a ‘never-Trumper.’ I have no problem with Youngkin…he’s united the base of the party.”

Despite Terry McAuliffe’s ceaseless charges and remonstrations, Glenn Youngkin is not Donald Trump. While Youngkin paid homage to the controversial-yet-unavoidable former president early in his campaign, crediting him as inspiration for his decision to run and centering his initial platform around election integrity, the moderate Republican businessman cultivated a much different public persona throughout the race. Youngkin’s trademark red vest, especially, became a symbol of his common-man, populist persona, and it undeniably gave him an edge among voters.

“Glenn Youngkin [brought me out today] because of what he stands for,” voter Father Thierry, 60, said at a Youngkin rally in Chesterfield County just days before the election. “His values speak to me…I’m an independent. I’m not a Republican; I’m not a Democrat. I’m a Christian.”

In a recent interview, McAuliffe senior advisor Michael Halle credited the Republican Party of Virginia for selecting Youngkin, a candidate he believes was uniquely suited to challenge McAuliffe — or, at least, a better choice than his many of his contemporaries.

“There were a couple other candidates that ran in the [Republican] primary that I think we would have beaten,” Halle said. “I think we would have beaten Amanda Chase; I think we potentially could have beaten Kirk Cox…I think Pete Snyder would have been very tough.”

And it’s also worth acknowledging that Glenn Youngkin is currently worth hundreds of millions of dollars, per a Forbes article published just this past year. While McAuliffe’s establishment connections allowed him to fundraise at an alarming rate, Youngkin needed less help from his allies, funneling tens of millions of dollars of his own money into his campaign over the course of several months. It absolutely gave him an edge.

“Frankly, I think if there was candidate ‘Nick’ that was running,” Halle said, “And had little record but could dump 20 million dollars, or 10 million dollars, or even probably eight-and-a-half million dollars of [their] own money into the race, it would have been the same outcome.”

And it’s not just political strategists who recognized the importance of Youngkin’s deep pockets, either. Many Virginian voters on both sides of the aisle saw the businessman’s immense self-contributions as potentially problematic for our democracy.

“I don’t know [if people are excited about this race],” food truck owner and veteran Lloyd Phillips, 71, said. “I’m afraid of this race. Republicans are spending a lot more money than the Democrats are, and it scares me…It’s all about the money. Money and power.”

Candidate Terry McAuliffe: Not Virginian

One could also make the argument that Terry McAuliffe, while a wonderfully experienced establishment politician, never truly seemed in sync with Virginian politics or values. And that makes sense since, despite years spent serving the state, he’s not actually from Virginia. It may seem harshly exacting to attribute any real influence on that fact, but politics are unavoidably just as much about what speaks to voters as they are about actual policy or political experience — and McAuliffe’s approach to certain issues, as well as his general mannerisms, failed to capture the hearts of many Virginian voters.

“I mean, Terry’s not the most inspiring, you know, person,” author and educator Cheryl Ware, 56, said at a McAuliffe event in Henrico County. “He’s sort of this used-car salesman-type guy. Personally, I voted for Jen McClellan in the primary, and I unenthusiastically voted for Terry.”

Jamie May, a 23-year-old analytical chemist and Starbucks manager, also voted for Terry McAuliffe despite an abiding love for Liberation Party candidate Princess Blanding. While he thought Blanding’s platform to be more in line with the issues he personally cared about, May recognized that McAuliffe was seemingly in dire straits, and ultimately prioritized keeping Virginia blue over voting his conscience.

“I care about keeping abortion relatively accessible, keeping trans and LGBTQ rights in the 21st century, homelessness and housing, and generally preventing us from turning into Texas,” May said. “I voted for Terry just because of the statistics.”

McAuliffe further exacerbated things with one off-handed comment about education, telling voters that he didn’t “think parents should be telling schools what they should teach.” Youngkin pounced on this statement immediately, and McAuliffe never apologized or walked it back — infuriating Virginian parents already frustrated by the pandemic’s impact on their children’s education. It’s difficult to understate how important this moment was, as it ultimately and almost exclusively defined the last few months of the race.

It feels safe to assume that the apparent disconnect between McAuliffe’s campaign and the more progressive members of his base caused problems for Democrats throughout the election. Whether that disassociation was the product of the poor campaign strategy or the wrong candidate, however, is another story — though it does seem as though McAuliffe’s team grossly underestimated Republican voter turnout on election day.

“We believed that the higher the turnout, the better the scenario for us,” Halle said. “The disproportionate turnout among Republicans is something we didn’t expect. I think we believed that the more nationalized the race — if we were exceeding 2017 numbers — the more likely we were to be successful…that was a miscalculation as well.”

On Monday night, just hours before election day, Terry McAuliffe cancelled his scheduled Virginia Beach appearance, citing low engagement and minimal expected turnout. For those of us on the ground in the state, the decision confirmed what many already felt in our guts: McAuliffe would not win reelection to the Virginia Governor’s Mansion. Despite a history of successful leadership in the state, ties to some of the most established Democrats in the country, and widespread name recognition, the career statesman had lost.

How did it happen? Like many failed campaigns, McAuliffe’s candidacy ended in a maelstrom convergence of poorly timed, unfortunate phenomena. Maybe the incorrect party nominee from the get-go, the career politician’s ties to a failing national Democratic establishment — compounded by an already-fickle electorate — prevented him from ever successfully countering or even truly responding to the uniquely captivating Republican nominee that was Glenn Youngkin.

In the end, McAuliffe lost to Youngkin by about 2.25 percentage points. Already, politicians and pundits around the country are assigning dramatic gravity to that outcome, advancing it as a portent of grave danger for Democrats in the 2022 midterm elections. That’s not necessarily the case. If, instead of fatalistically harnessing this gubernatorial election to rationalize expected national defeat, Democrats use it as a chance to get back in touch with their base and rethink their systems, they can find a silver lining. If Democrats want to win over American voters, they need to implement ranked choice voting, run on platforms and policies that Americans actually care about and support, and use political power to make things happen. It’s that simple.