Senator Bernie Sanders will not be, now or ever, President of the United States of America. The senator suspended his campaign earlier today, ending his second presidential bid in five years and clearing the path to the Democratic nomination for former Vice President Joe Biden. It’s a decision that marks the end of a historically complex primary season; even without Sanders’ outright endorsement, Biden looks set to challenge Trump on behalf of the DNC this November.

I’d like to honor Sanders’ capitulation with a broad assessment of his larger campaign failings. For all that I believe the Senator gets right — and I do believe he gets a lot right — Sanders has made some decisively poor decisions throughout his campaign. I hold that these decisions are tied to a much larger partisan political landscape, and will attempt to explain these connections succinctly in the following piece.

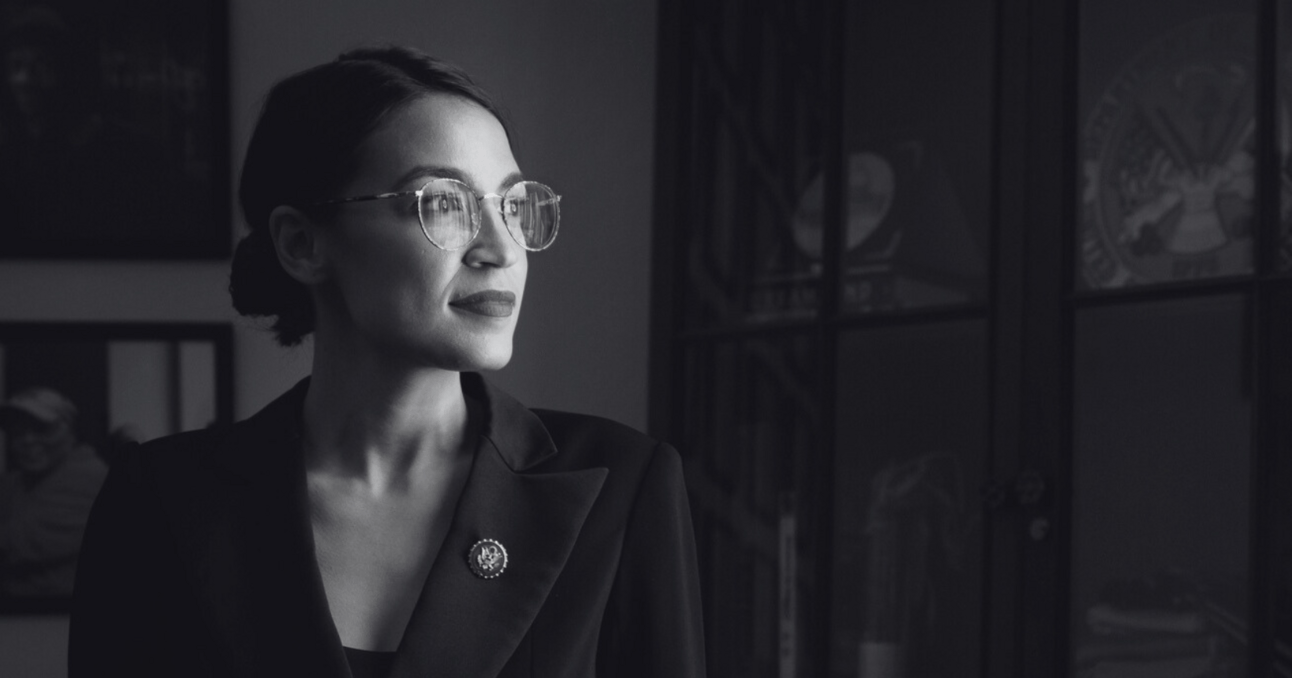

I plan on addressing three different, and yet inextricably connected, phenomena: the current state of our preternaturally polarized political public, lessons learned from Sanders’ dual presidential bids, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s burgeoning neoteric progressivism. I speculated two years ago that we were farther from a progressive renaissance than many thought-it’s disappointing, albeit slightly satisfying, to confirm those suspicions now.

Hardening Regime Cleavage

Our national two-party political system is marked by uniquely American radicalization. I’ve spent the last year and a half studying affective political polarization across the nation, and come to the singular conclusion that we’re all in trouble. Our electorate is currently radicalized to an almost unprecedented degree; even our social lives are now affected by a political divide. One recent study indicates that Americans are actually less likely to spend time together in cross-partisan families, estimating that we lost 34 million hours of conversation in 2016 alone.

Republicans and Democrats have fought over the same things for decades: whose values and policies best support American democracy. Now, those fights are changing — disagreement over pragmatic solutions has evolved into disagreement over our founding democratic principles themselves. Though now buried amidst a concluding Democratic primary season and a global pandemic, President Donald Trump’s impeachment just months ago demonstrated clearly this conflict over constitutional legitimacy: White House refusal to cooperate with multiple congressional subpoenas sets a dangerous precedent, even as the administration’s communications team trumpeted the illegitimacy of the impeachment inquiry itself.

Such intense structural political disagreement is symptomatic of a much larger phenomenon — regime cleavage. Popularized by political scientists, the term refers to any division within a population grounded in conflict about the foundations of governing systems themselves. It’s easy behavior to characterize, and a kind that has occurred infrequently in recent American history (prolonged debate about the constitutionality of the Second Amendment epitomizes this phenomenon) but that is now more pronounced than ever before.

Case in point: Brett Kavanaugh, the most recent addition to our Supreme Court, is on record defending the immunity of our sitting president to special investigation. Kavanaugh’s controversial confirmation consequently foreshadowed growing unrest, challenging the system of checks and balances that safeguards our democracy. More dishearteningly, the percentage of those who opposed the House impeachment inquiry matches the percentage of those who approve of the president — indicating clear partisan divide over political legitimacy. Trump routinely reinforces this gap, indiscriminately labelling his opponents disloyal, un-American, or even treasonous. White House messaging and behavior suggests blatant indifference to our institutionalized systems, including the Constitution, and indicates to supporters that it’s not just the DNC but our national democracy itself that is the problem.

There are consequences of regime cleavage. If enough of the public is persuaded that it’s okay to bypass or simply ignore institutionalized checks on executive power, or lose faith in our electoral processes altogether, it green-lights further attacks on the independence of our judiciary or further degradation of our federal separation of powers. We’ve witnessed regime change run rampant before, both globally and domestically, and it never ends well. Argentina, Chile, Taiwan — left unchecked, this radical fundamental polarization leads almost directly to militarized violence and forced regime change. It was our last experience with regime cleavage, after all — a refusal by slave states to recognize federal legitimacy — that resulted in the bloodiest civil war ever fought.

Nixon’s presidency ended in scandal after Watergate. It ended because we collectively recognized the need to respect rule of law, and united across party lines to uphold our guiding democratic principles. Now, once again, our entire democratic system is under attack. It’s imperative that we recognize this polarization as the pronounced danger it is, and work to rectify it immediately.

Lessons From Sanders’ Campaign[s]

So — what does any of this have to do with Senator Sanders’ two failed presidential bids, or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s burgeoning neoteric left-wing progressivism?

President Ronald Reagan’s legacy is twofold, and has defined the Republican political project for the last fifty years. The GOP now fights to do two basic, primary things: to firmly ingrain trickle-down economics in the American psyche, and to metaphorically starve the governmental beast.

Of course, persuading the broad public to revolt against their own representative democratic government is no easy task. It necessitates a large-scale public relations campaign — an assault on the national psyche designed to degrade public trust in electoral processes and thus enable the draconian undercutting of governmental oversight. Such has been the conservative project for decades. It came to fruition with Trump’s election; the populist campaign slogan “drain the swamp” perfectly encapsulates this Republican platform — that our government is ineffective at best, that it is malicious at worst, and that we must winnow its powers to preserve our national democracy. GOP campaigning is designed to convince us that the government fails to do its job: This is the genesis of regime cleavage, that conflict over basic integral government function, and the inception of broad political malaise.

Senator Bernie Sanders chose to embrace that malaise. Sanders fed into this conservative agenda even as he countered it; it’s no coincidence that the senator’s movement still draws direct comparison to the Tea Party. Campaign messaging positioning Sanders as President Trump’s pure-hearted foil came at a cost: Suggesting to supporters that everything in the political establishment is bad, minus Sanders himself, reinforces age-old conservative ideology.

It’s clear now that, despite protest from die-hard supporters, Sanders never truly did enough to welcome those disillusioned voters into his campaign. This is the hard truth: Sanders failed. For all his talk of unity and coalition building, for all talk of the Senator’s ability to cross party lines and work with opponents, Sanders failed. Those same groups he and his base routinely pointed to as evidence of electability — youth, Black voters, independent voters — disappeared en masse when it came time to vote.

Sanders’ base loves him — just not as much as they hate, or think they hate, the current political establishment. It’s become markedly clear that this political thought accounts for much of Sanders’ 2016 support; the Senator’s state-by-state support this primary season drastically differs from his support in the last cycle, indicating that much of his strength then was fueled solely by anti-Clinton sentiment (Hillary Clinton being, unarguably, the perceptive embodiment of liberal establishment politics). Just look at Michigan — despite winning the state in 2016, Sanders lost every single county to Biden this year.

Senator Bernie Sanders is a wonderfully moral politician with some observably unarguable shortcomings. Sanders’ almost naïve lack of political coalition building praxis manifests as idealistic shortsightedness that sabotages his work. Those unique qualities that endear Sanders to so many — that endear him to me — are both refreshingly urgent and devastatingly imprudent. Take, even, the senator’s recent comments concerning Fidel Castro. Though I’m inclined to agree with Sanders’ assessment (it would in fact be “unfair” to suggest that “everything is bad” about Cuba’s Communist revolution), I also understand that voicing that opinion in a public forum is a severe political misstep. Sanders unnecessarily alienated an enormous faction of Cuban Floridian voters at a time when he desperately need an electoral win, and it’s this approach to speaking truth to power that hurts him.

Sanders’ problem is, and always has been, that he lets his moral compass override his political savvy. It’s what makes him an irrepeatably captivating candidate, but also what costs him elections.

Ocasio-Cortez & Neoteric Progressivism

Politico recently ran an article accusing AOC of breaking with Sanders’ ideological approach. Alex Thompson and Holly Otterbein point to AOC’s seeming reluctance to endorse Justice Democrats-backed incumbent primary challengers, turnover of top aides in the representative’s congressional office, and cooperation with Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi as evidence of this split.

AOC is not “breaking” or “splitting” with Sanders, though I do think Thompson and Otterbein get a lot right in their piece. AOC is adapting. Here is the encouraging silver lining to Sanders’ campaign mistakes: Others will learn from them. AOC isn’t being coopted by the Democratic system, but vice cersa — she’s coopting it for her own use. Her withdrawal of plans for a “corporate-free” caucus, among other political maneuvers (including the creation of a new PAC focused on electing progressives in Republican-held or open seats), indicates not that AOC is caving to the establishment, but that she is shaping her own neoteric left-wing progressive movement. “She’s speaking in a way to create a majority in a way that Bernie is not interested in doing,” says Max Berger, the former director of progressive outreach for Elizabeth Warren. Moreover, Justice Democrats aides remain steadfast in their support of AOC and her work even as speculation swirls around the departure of Chief-of-Staff Saikat Chakrabarti and Communications Director Corbin Trent.

AOC isn’t compromising her ideology, or regressing into establishment praxis. She’s adapting to and learning from the mistakes of her heroes to create a cohesive and practical neoteric left-wing radicalism. If anything, AOC is to be lauded for her clear-headedness and willingness to remodel her political movement.

It is, I think, a pretty clear arc: Reagan’s conservative project birthed the conditions for distinct regime cleavage. Instead of recognizing these conditions and combating them, Sanders embraced them, attempting to warp them to his benefit. In doing so, he fostered widespread disillusionment with the political establishment while simultaneously failing to harness that same disillusionment for his own movement. Sanders’ suspension of his campaign is pointed evidence that his idealistic approach to consolidating political power is earnestly flawed; evidence that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is now acknowledging as she begins her own neoteric left-wing progressive campaign. It’s heartening to see AOC learn from the mistakes of her heroes, given that those mistakes that cost us a morally-righteous presidency.

I’d like to address one more contemporary phenomenon: the Biden naysayers. I’m seeing, even now as I scroll through my social media, an overwhelming number of Sanders supporters lamenting or viciously condemning us to another four years of a Trump presidency. I wouldn’t be so sure. Yes, Sanders beat Trump in head-to-head polling — but so does Biden. Biden is clearly and unarguably, like it or not, coalition building like no other Democratic candidate can. I don’t think it wise to cling to broad theoretical notions of Sanders’ electability — or conversely, Biden’s lack of electability — when Sanders has lost two presidential primaries. If Sanders is so much more electable than Biden, why couldn’t he beat him in the primary?

Biden is beating his Republican incumbent opponent, Trump, in almost every poll. He beat Sanders, as well as a host of formidable opponents, for the Democratic nomination. It’s borderline hysteric to, at this point in time, call any election outcome inevitable — especially when doing so only serves to self-satisfy a now-irrelevant and observably mistaken point about candidate electability. It’s time to coalesce around Biden, for better or worse, and to vote not your personal conscience but our national conscience come November.